Energy from the sea

Introduction

Energy of the sea comes from different sources:

the sun, either indirectly due to the wind that gives rise to waves, or directly due to the thermal gradient between the surface of warm seas and deep water, which is used to operate a low temperature difference thermodynamic cycle. This is known as ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC). Conversion devices are still, in both cases at the prototype stage;

gravitation, because of the relative movements of the earth, moon and sun, creating tides. This is called tidal energy. However, few sites can cross the threshold of profitability for these facilities. In France, the La Rance plant was commissioned in 1966. It has 24 bulbs and produces 10 MW 0.5 TWh / year (figure below).

Ocean thermal energy conversion

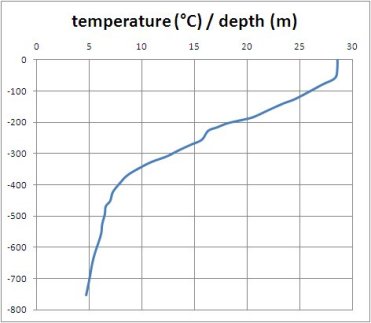

OTEC cycles are designed to generate electricity in warm tropical waters using the temperature difference between water at the surface (26-28 °C) and at depth (4-6 °C), from 1000 (figure below).

Two main types of cycles are used: closed cycles and open cycles, invented by two Frenchmen, respectively Jacques d'Arsonval in 1881 and his student Georges Claude in 1940, who proceeded to a first experiment.

In all cases, the need to convey very high water flow rates and pump cold water at great depth induces significant auxiliary consumption. Optimization of an OTEC cycle is imperative to take into account those values.

Although technically valid, OTEC cycles are not yet economically viable. Prototypes of various capacities have been realized or are being considered, including in Hawaii and Tahiti.

Closed cycles use hot water at about 27 °C to evaporate a liquid that boils at a very low temperature, such as ammonia or an organic fluid. The produced vapor drives a turbine, and is then condensed by heat exchange with cold water at about 4 °C from deeper layers of the ocean.

The thermodynamic cycle is an intermediate Hirn cycle, whose modeling poses no particular problem. The design of heat exchangers is of course even more critical given the very small temperature difference between hot and cold sources. The values of pinches should be as low as possible while remaining realistic.

In open cycles, the warm water at about 26 °C is expanded in a low-pressure chamber (called flash), which allows to evaporate a small fraction (around 5%). The produced steam drives a turbine and is condensed in a low pressure chamber by heat exchange with cold water at about 4 °C from deeper layers of the ocean. The condensate is virtually pure water, which can be used for food.

The open cycle thus has the advantage of producing both electricity and fresh water, but the very low expansion ratio involves implementing very large turbines. It involves five elements: a flash evaporator, a turbine, a condenser, a basin for collecting the used seawater, and a vacuum pump.

Additional information

A guidance page for practical work explains how to model these two types of cycles.